Hands-Free Database Access from Vivino

There is a cool new app out of Denmark called Vivino, that besides being just plain useful, also offers a great working example of both mobile visual interaction with database content.

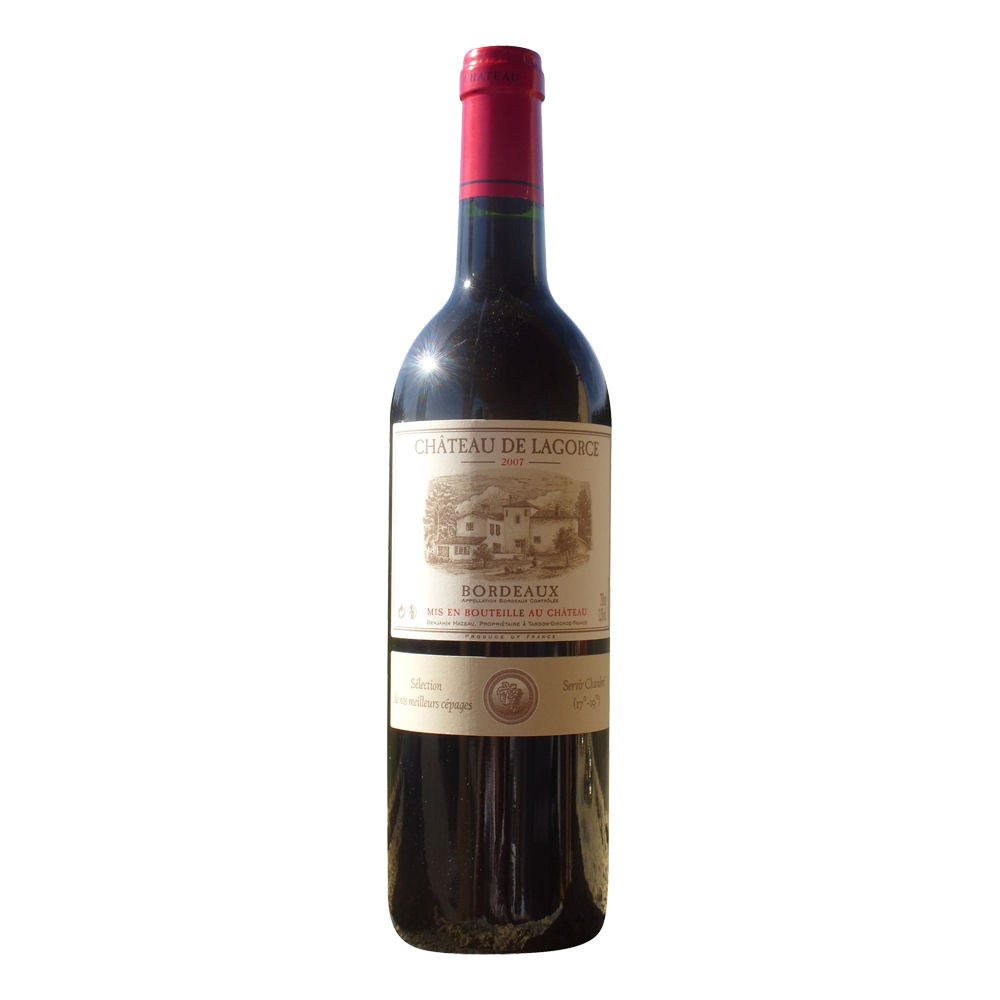

Vivino lets you use your smartphone camera to take a picture of the label on any wine bottle, and have returned to you complete information about the wine. Yes, it’s a true hands-free database query.

There is a cool new app out of Denmark called Vivino, that besides being just plain useful, also offers a great working example of both mobile visual interaction with database content.

Vivino lets you use your smartphone camera to take a picture of the label on any wine bottle, and have returned to you complete information about the wine. Yes, it’s a true hands-free database query.

The data can be used strictly for educational purposes, as a way to learn more about a particular wine. At the same time, its point-of-sale implications are huge.

The heart of the technology is image recognition software that can match the photograph of a wine label to Vivino’s standing database of over 450,000 wine label images. And the database is not just for look-ups: if you like a wine, just flag it in the database with the push of a button, and the system remembers it for you.

Another feature, apparently still under development, is the use of your geo-location to identify nearby wine stores. And of course Vivino has the requisite social sharing features.

What’s also of interest to data publishers is that if Vivino can’t match a wine label, it manually researches it using its own research staff, and sends the information to the user once it makes a match. That has the triple benefit of engagement, enhancing user satisfaction and expanding the database.

Vivino is still in beta, but monetization options are plentiful. It’s worth noting that the wine database space is very crowded, but there doesn’t yet seem to be a dominant player. And if you picture yourself in a wine shop, you can see the innate appeal of being able to snap a picture and get a full profile on any bottle of wine. This is a truly powerful and productive use of mobile technology.

Vivino provides an eye-opening insight to all data publishers: sometimes you can make your existing dataset more valuable just by enhancing the ways users can access it. This is doubly important in mobile applications, where large fingers and small keys rarely make for a satisfying user experience.

IDG-Linkedin Partnership: Re-Defining Publishing?

Just yesterday, the major business publisher IDG, through its Custom Solutions group and its ComputerWorld, InfoWorld, CIO and CSO media properties, announced a partnership with LinkedIn to create “targeted marketing opportunities for b-to-b brand marketers.” So what does this partnership means? It appears that IDG will sell to its advertisers the right to sponsor an IDG owned and operated LinkedIn group on either a specific IT-related topic, or a custom LinkedIn group likely tied to things such as new product launches. In the latter case, the advertiser controls the direction of the group.

On its face, this seems like a clever sponsorship idea. But then you might ask why does IDG need to partner with LinkedIn to create a LinkedIn group? Anyone can do that. For that matter, why does the advertiser need IDG to create a LinkedIn group? The answer is partly content, and mostly audience. And here’s where it gets interesting.

LinkedIn’s role in this partnership, according to Folio, is to “be responsible for promotion, content distribution and member recruitment.” Yes, LinkedIn is going to be supplying both audience and content distribution. What IDG is bringing to the table is the advertiser, the content and management of the group.

Traditionally, the role (and much of the value) of the publisher was building an engaged, target audience and charging to deliver messages to it. Here, both the audience and the distribution platform no longer belong to the publisher.

I’m not disparaging this deal; indeed it has hints of brilliance showing through. But what intrigues me is that LinkedIn, a professional network and data content company, can now so effectively perform most traditional publishing functions.

While I admire LinkedIn for building the most important biographical database in the world (still the primary source of its revenue), it is also both a powerful network and content distribution platform. LinkedIn groups thrive for tens of thousands of specialized audiences, and LinkedIn has shown real talent in selective news distribution to users. LinkedIn has all the elements necessary to be a major publisher in its own right. To date, however, it has chosen to be a platform rather than a publisher.

It’s likely we will see a greater shifting and blurring of roles over time. Already, we have examples of companies that leverage LinkedIn groups to build publishing and events companies. And IDG shows us here an example of a successful publisher leveraging the power of the LinkedIn platform.

I don’t see LinkedIn trying to muscle itself into B2B publishing, but I think this is the first indication of a profound re-definition of the publishing business. This is not necessarily bad news, but if you thought things were settling down, you better fasten your seat belt.

The Gamification of Data

I attended the Insight Innovation Conference this week – a conference where marketing research professionals gather to think about the future of their industry. A number of the sessions dealt with the topic of gamification. Marketing research is really all about gathering data, and a lot of that data is gathered via surveys. And, not surprisingly, market researchers are finding it harder than ever to get people to participate in their surveys, finish the surveys even when they do participate, and supply trustworthy, high quality answers all the way through. It’s a vexing problem, and it is one that is central to the future of this industry.

That’s where gamification comes in. Some of the smartest minds in the research business think that by making surveys more fun and more engaging, they can not only improve response rates, but actually gather better quality data. And this has implications for all of us.

One particularly interesting presentation provided some fascinating “before and after” examples of boring “traditional” survey questions, and the same question after it had been “gamified.” As significantly, he showed encouraging evidence that gamified surveys do in fact deliver more and better data.

And while it’s relatively easy to see how a survey, once made more fun and engaging, would lead people to answer more questions, it’s less obvious how gamification leads to better data.

In one example, the survey panel was asked to list the names of toothpaste brands. In a standard survey, survey respondents would often get lazy, mentioning the top three brands and moving to the next question. This didn’t provide researchers with the in-depth data they were seeking. When the question was designed to offer points for supplying more than three answers and bonus points for identifying a brand that wasn’t in the top five, survey participants thought harder, and supplied more complete and useful data.

In another example, survey participants were given $20 at the start of the survey, and could earn more or lose money based on how their responses compared to the aggregate response. Participation was extremely high and data quality was top-notch.

Still other surveys provided feedback along the way, generally letting the survey participants know how their answers compared to the group.

Most intriguing to me is that gamification allowed for tremendous subtlety in questions. In a game format, it’s very easy to ask both “what do you think” and “what do you think others think,” but these are devilishly hard insights to get it in traditional survey format.

Gamification already intersects with crowdsourcing and user generated content quite successfully. Foursquare is just one well-known example. But when the marketing research industry begins to embrace gamification in a big way, it’s a signal that this is a ready-for-prime-time technique that can be applied to almost any data gathering application. Maybe it’s time to think about adding some fun and games!

Is Data the Salvation of News?

Doubtless by now you’ve heard the buzz around the travel news start-up called Skift. Skift is the brainchild of Rafat Ali, the founder of PaidContent. Skift appears to be a disruptive entry into the B2B travel information market, and seeks to distinguish itself through a fresh style of reportage and eclectic editorial coverage (news of innovative airport design merits the same level of coverage as news about major airlines). Given Rafat’s track record and the fondness these days for all things disruptive, Skift has recently attracted an additional $1 million from investors. Where this gets really interesting is that Skift wants to broadly cover the incredibly huge global travel industry with only a handful of reporters. That means Skift will deliver a mix of original reporting along with licensed and curated content. So where’s the innovation and disruption? The answer, in a word, is data.

Skift’s plan is to deliver most of its news free on an advertising-supported model, but to also offer paid subscriptions (reportedly to range from $500 to $1,000) to give subscribers access to travel data. It’s no surprise then, that Skift is positioning itself as a “competitive intelligence engine.”

Skift may be on to something. I first got interested in the intersection of news and data back in 2007, when I read some fascinating articles written by Mike Orren, the founder of an online newspaper called The Pegasus News. Orren had discovered that despite his focus on hyper-local news, the editorial content that consumers are ostensibly hungering for, fully 75% of those who came to his site were there for some sort of data content. Others in the newspaper industry have also reported similar findings.

In this context Skift seems to have a firm grasp of the new dynamics of the information marketplace: while there is an important role for news, it’s increasingly hard to monetize. That’s why news married to data is a much smarter business model. News provides context and helps with SEO. It can be monetized to some extent through advertising. Data offers premium value that is easily monetized with a subscription model, and the two types of content, intelligently combined, offer a compelling, one-stop proposition to those who need to know what’s going on in a specific market.

This is, of course, a conceptually simple model that not too many legacy news publishers have been able to execute on. That’s because the two types of content are inherently distinctive, from how they are created to how they are sold. Perhaps a disruptive market entrant like Skift will be able to crack the code and produce both types of content successfully itself. Personally, I think the fastest and surest path to success is to build strong partnerships with data publishers.

Google: An Unstable Platform

Google appears to be near a settlement with European Union regulators over alleged anti-competitive practices there. A broad outline of the proposed remedy for this activity is beginning to emerge, and it’s fairly remarkable.

The remedy has two parts. First, all Google services that appear in search results would appear in a separate box and be labeled as sponsored content. Even more remarkably, Google would be required to show search results for up to three of its competitors whenever it displays a result containing one of its own services.

over alleged anti-competitive practices there. A broad outline of the proposed remedy for this activity is beginning to emerge, and it’s fairly remarkable.

The remedy has two parts. First, all Google services that appear in search results would appear in a separate box and be labeled as sponsored content. Even more remarkably, Google would be required to show search results for up to three of its competitors whenever it displays a result containing one of its own services.

Now before you get too excited, remember this settlement only applies to Europe. Don’t expect to see it in the United States anytime soon, if ever.

The core issues underlying this settlement are intriguing. Can a search engine be accused of anti-competitive behavior for favoring its own services in search results? The publisher in me says “yes,” because Google is rolling out more and more content, and it has a massive, unfair advantage over any publisher it competes with.

Google would probably respond to this by saying its dominance in search comes from providing really good search results, and that’s what will ultimately constrain its behavior. If Google gets too cute with users by pushing its own products too aggressively, users will desert it for another search engine. I buy this argument to some extent, but it also downplays the power of user habituation, and Google’s unique ability to promote its own products inside seemingly organic search results.

I know more than a few publishers who have woken up in the morning to find their traffic - and by extension their businesses - had dried up because Google had tweaked its search algorithms. I know why Google did this, and agree they should have the right to do this. But it leaves a trail of wreckage in its wake. And Google’s seemingly accelerating push into the content business seems likely to have the same effect.

The bottom line is that Google has evolved over the years, and consequently publishers need to evolve in their thinking towards Google. The term “frenemy” was coined to summarize our confusion about how we should best interact with Google. The emerging reality seems to be that while Google can still bring benefit to all of us, it’s a mistake for any of us to depend on Google for our business. That’s a big statement to make, but from both a strategic and operational perspective, Google is an unstable platform.