The Hidden Data in Invoices

The data business is one of creativity, and what could be more creative than asking companies to send you their invoices and other types of billing data so you can get them into a database and sell the aggregate results back to them? Now, why would something like this ever make sense? Well, in many industries, there is nothing more useful or important than pricing information. Yet the pricing information that many companies publish (if they publish it at all) is almost always the list price. And in many industries, the list price is close to meaningless, since every customer will have a special deal and varying discount. So how do you develop a database of what companies are really paying for specific products and services? Ask to see their invoices!

There are lots of spins on this intriguing model, so let’s take a look…

The question already on your mind quite likely is, “Why would any company let me look at its invoices?” The simple answer is what I often refer to as “strength in numbers.” A company will happily give up its individual data (properly secured and anonymized) in exchange for access to the aggregate results. And they’ll pay for that access, and that’s exactly the play here.

A great example of collecting, normalizing and reporting out information drawn directly from the internal systems of advertising agencies can be found in a company called SQAD. Its NetCosts product collects data for media purchases from advertising agencies worldwide, generating what may be the only honest look at what broadcasters are charging for media buys, and even what they have charged into the future. You can immediately see how valuable this information can be.

Thomson West has a product called Peer Monitor that does the same thing in a slightly different way: rather than work with the recipients of invoices, it works with the senders of invoices, in this case law firms, to collect similar data to be used in similar ways.

If it sounds like a lot of work, it is, or probably was. That’s because SQAD now receives most of its purchase data digitally, through interfaces with client systems. And while those interfaces were doubtless painful to build, at the same time SQAD has built an almost impregnable franchise, because as long as SQAD doesn’t get greedy, nobody can justify the time, cost and pain to try to compete with them. The same holds true for Peer Monitor.

There’s also what might be called the pre-order model. Here, your objective is to gather RFPs and proposals to get a true look at what companies are proposing to charge for their products. One advantage of picking up information at this stage is that there is often a lot more detail, allowing you to collect even more granular product price data. A great example of this model is MD Buyline, a company that collects price quotes and proposals on medical equipment to build a high-accuracy pricing database.

Lots of variant models, but the objective is the same: gather data on actual prices being charged in the marketplace, the more granular the better. Your job is to aggregate, normalize, and report back to the marketplace, while protecting the anonymity of those who participate.

It’s important to note that the need for pricing data isn’t equally compelling in every market. The dynamic seems to be a reasonably large pool of both buyers and sellers, and a solid tradition of haggling over price. It won’t work for everyone, but it’s certainly worth considering if it would work in your market.

A Business Model Detour

TrueCar.com started out as a data and analytics company, offering insight to consumers as to the actual prices being paid for specific makes and models of cars in their local area. The idea was to aggregate multiple data sources, including actual sales data from dealers themselves to build as much precision as possible into this pricing information. In many respects, TrueCar was duplicating the approach taken by established industry powerhouse Edmunds.com. What TrueCar didn’t duplicate was the business model of Edmunds. Indeed, TrueCar took an entirely different route.

TrueCar moved beyond providing estimates of new car prices to delivering actual prices that dealers would accept. Simply hand your TrueCar number to the dealer, and the car would be yours for that price. It was a fresh approach, and particularly compelling to those consumers not fond of haggling with car dealers.

The idea took off. TrueCar signed up thousands of dealers to accept its pricing. Then, according to published reports, it started marketing itself as offering the lowest prices for new cars. Turns out, its dealers weren’t thrilled with that positioning, in large part because they weren’t offering the lowest prices, and large numbers of them canceled their affiliation with TrueCar.

TrueCar recovered from this, but in an odd way. It now represents itself as offering “fair prices” instead of lowest prices. And from a quick look at its site, you can see that it has morphed into a lead generation service for car dealers. I asked for a price on a car from dealers near my zip code and was presented with three prices from three dealers. That’s a big move away from presenting objective pricing based on aggregated sale price and other data.

So, the TrueCar value proposition has pivoted from providing objective data to providing consumers with a price in advance that certain dealers will honor, thus avoiding the stress and uncertainty of having to negotiate a price. If you look at the TrueCar website now, you’ll be repeatedly assured you are getting a fair, competitive price, but if there’s any data to back up that claim, the company’s no longer talking about it.

TrueCar claims to be responsible for 2.3% of all cars sold annually in the United States, so it seems to have tapped into a real need in the marketplace. At the same time, it’s a rare pivot away from a data-driven business model, to a model that as far as I can see doesn’t require any data at all.

Of course there’s a great lesson here in profiting from adversity, but there’s another lesson here as well: if you dive into the data business without a clear business model, you’ll probably find yourself needing to make an expensive and dangerous u-turn.

Hands-Free Database Access from Vivino

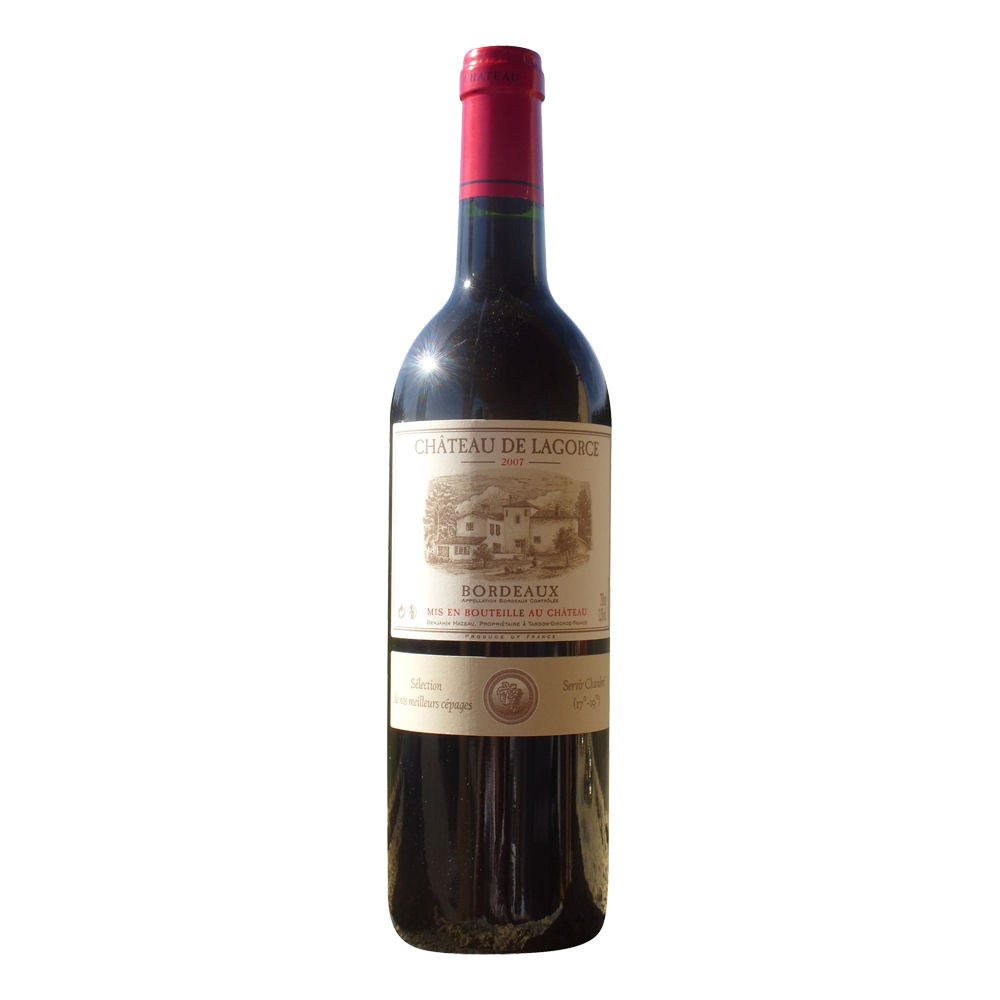

There is a cool new app out of Denmark called Vivino, that besides being just plain useful, also offers a great working example of both mobile visual interaction with database content.

Vivino lets you use your smartphone camera to take a picture of the label on any wine bottle, and have returned to you complete information about the wine. Yes, it’s a true hands-free database query.

There is a cool new app out of Denmark called Vivino, that besides being just plain useful, also offers a great working example of both mobile visual interaction with database content.

Vivino lets you use your smartphone camera to take a picture of the label on any wine bottle, and have returned to you complete information about the wine. Yes, it’s a true hands-free database query.

The data can be used strictly for educational purposes, as a way to learn more about a particular wine. At the same time, its point-of-sale implications are huge.

The heart of the technology is image recognition software that can match the photograph of a wine label to Vivino’s standing database of over 450,000 wine label images. And the database is not just for look-ups: if you like a wine, just flag it in the database with the push of a button, and the system remembers it for you.

Another feature, apparently still under development, is the use of your geo-location to identify nearby wine stores. And of course Vivino has the requisite social sharing features.

What’s also of interest to data publishers is that if Vivino can’t match a wine label, it manually researches it using its own research staff, and sends the information to the user once it makes a match. That has the triple benefit of engagement, enhancing user satisfaction and expanding the database.

Vivino is still in beta, but monetization options are plentiful. It’s worth noting that the wine database space is very crowded, but there doesn’t yet seem to be a dominant player. And if you picture yourself in a wine shop, you can see the innate appeal of being able to snap a picture and get a full profile on any bottle of wine. This is a truly powerful and productive use of mobile technology.

Vivino provides an eye-opening insight to all data publishers: sometimes you can make your existing dataset more valuable just by enhancing the ways users can access it. This is doubly important in mobile applications, where large fingers and small keys rarely make for a satisfying user experience.

People Power

There was news this week about the formation of Bloomberg Beta, a new venture capital fund sponsored by data company Bloomberg LP. One of Bloomberg Beta’s early investments is a company called Newsle, that will alert you whenever someone you specify – a friend or colleague – is in the news. This is a tough nut to crack. Searching thousands of news sources and trying to determine if the John Smith mentioned in an article is the same John Smith of interest to you is a complex undertaking. But what really intrigued me is that those who have written about Newsle see another major problem that the company faces: lack of activity. Think about it. If you import your list of Facebook friends (something Newsle encourages you to do), the chances of any of them appearing in news stories is pretty low. That means most people will sign up for Newsle and nothing will happen, not because Newsle isn’t working, but because there is no news to report. It’s hard to establish the value of your service if you’re not delivering at least a little something every now and then.

That’s why in addition to your Facebook friends, Newsle also encourages you to import your LinkedIn contacts, and while you are at it, your address book as well. Somewhat incongruously, Newsle also encourages you to follow politicians and celebrities. The hope is the more people you track, the more likely you’ll get hits.

But what if Newsle flipped its model? Instead of serving individuals who for the most part have small lists of mostly boring contacts, why not hook up with commercial data publishers, many of whom have tens and even hundreds of thousands of contacts in their databases? Publishers could then send real-time alerts out to their subscribers who are interested in specific people or any activity relating to executives at a given company. In addition to sales intelligence, these news alerts could also provide a basis for making contact with a prospect. Plus, publishers could database these news events to build deep profiles on company executives that would have evergreen value.

This could be a great opportunity for Newsle to crack its volume problem, and for data publishers to add in high-value alerting services and historical data all in one fell swoop.

That’s powerful, people!

Enigma: Disrupting Public Data

Can you actually disrupt public data, which by definition is public, and by extension is typically free or close to free? Well, in a way, you can.

A new start-up called Enigma, which can be thought of as “the Google of public data,” has assembled over 100,000 public data sources – some of them not even fully or easily accessible online. Think all kinds of public records from land ownership, public company data, customs filings, private plan registrations, all sorts of data, and all in one place.

A new start-up called Enigma, which can be thought of as “the Google of public data,” has assembled over 100,000 public data sources – some of them not even fully or easily accessible online. Think all kinds of public records from land ownership, public company data, customs filings, private plan registrations, all sorts of data, and all in one place.

But there’s more. Enigma doesn’t just aggregate, it integrates. That means it has expended tremendous effort to both normalize and link these disparate datasets, making information easier to find, and data easier to analyze.

The potentially disruptive aspect to a database that contains so much public data is that there are quite a few data publishers with very successful businesses built in whole or in part on public datasets.

But beyond the potential for disruption, there’s some other big potential for this (I’ve requested a trial, so at this point I am working with limited information). First, Enigma isn’t (at least for now) trying to create a specific product, e.g. a company profile database. Rather, it’s providing raw data. That will make it less interesting to many buyers of existing data products who want a fast answer with minimum effort. But it also means that Enigma could be a leveraged way for many data publishers to access public data to integrate into their own products, especially since Enigma touts a powerful API.

The other consideration with a product like this is that even with 100,000 datasets, it is inherently broad-based and scatter-shot in its coverage. That makes it far less threatening to vertical market data publishers.

Finally, Enigma has adopted a paid subscription model, so it’s not going to accelerate the commoditization of data by offering itself free to everyone and adopting an ad-supported model.

So from a number of angles, this is a company to watch. I’m eagerly waiting for my trial subscription; I urge you to dig in deep on Enigma as well.